Spring 2021 saw visual artist Caroline Cardus become our latest artist in residence, collaborating with Barnsley’s disabled community to create The Barnsley 15 a public art project now installed in Mandela Gardens. This was a continuation of The Way Ahead which first came to life 17 years ago and uses the subversion of familiar symbols to explore the barriers disabled people face at home and work. Jason, at the Civic sits down with Caroline over Zoom.

How have you used your downtime during lockdown?

“I have been learning new design software. Because my work quite often involves text, in the past I’ve had to work with a graphic designer, but I quite liked the idea of learning something during lockdown that would boost my independence and what I could do in my practice. I think it’s important to carry on learning throughout your creative career. The pandemic has actually encouraged me to learn new things, and in turn has given me so many more new projects.“

When was the first time you really noticed that the barriers created by society would impact on your life as a woman with a physical impairment?

“I think from childhood really. I remember I was 12 and the impairment I was born with had gotten much worse. I had some major mobility issues. I had these horrible crutches that came right up to your elbows and you had to keep them in place by squeezing your armpits. I had blisters under my armpits. I had my leg in plaster for about eight weeks.

I lived pretty much outside my local school and I remember they had some roadworks right across the main school gates, so they shut them and I had to walk around the school perimeter to the back entrance and when you’re on elbow crutches, that’s really hard.

I asked my mum if she would drive me round to the back. At first she was like, are you kidding me? But the school wouldn’t allow me in through the front. That really was an early insight into the fact that a very small distance to any able-bodied person, can be more difficult or even impossible when you’re disabled. It wipes you out or it can cause major damage. After a couple of days, I had such bad blisters on my hands and under my arms that my mum completely understood and I got a lift while the roadworks were going on. That scene has played over many times since, whether it’s fatigue or mobility related, you realise that the majority of the world cannot understand how much effort you need to put into doing something that they would do without a second thought.”

It’s also the figuring out of stuff as well because giving up cannot be an option. You always must find other ways of doing things. People in disability arts are great creative thinkers and are incredibly innovative. Disabled people in general are incredibly innovative and always have to modify what they do.”

When was the first time you realised that activism could or would play a part in your art practice?

“At university, I made work about some difficult experiences I had that stemmed from being somebody with a genetic impairment, which hadn’t then been fully diagnosed. When I was growing up, my mobility issues were more hidden and were harder to articulate. At university, I studied Fine Art and I had this great tutor called Ron Wilman. He showed me lots of artists who were making work about Feminism or struggle. I remember making collages that were about mental health. I was also really interested in magic and ritual.

I’d had some counselling by this point. Mental health is something that disabled people might not talk about very much as it is not as visible as a physical disability. But mental health problems are very much present and that is very true for me. During this time, I was given books about being proactive and mental wellbeing. I liked to mix those up with collages and themes of magic. I didn’t think anybody would understand but it opened up conversations with people which was precious. And this was in the 90s; people did not talk about mental health when I was a student. It was difficult to talk about physical disability and access on campus, let alone mental health and the impact that the lack of access has on that. I thought I could be onto something here.”

What is the first piece of art you saw that resonated with you?

“My mom is a creative person. And when we grew up, we had a print of Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire opposite our dining table. I loved the abstract nature of it and the shimmering light. That would probably be the first work that I really loved looking at.”

But what about once you started studying art?

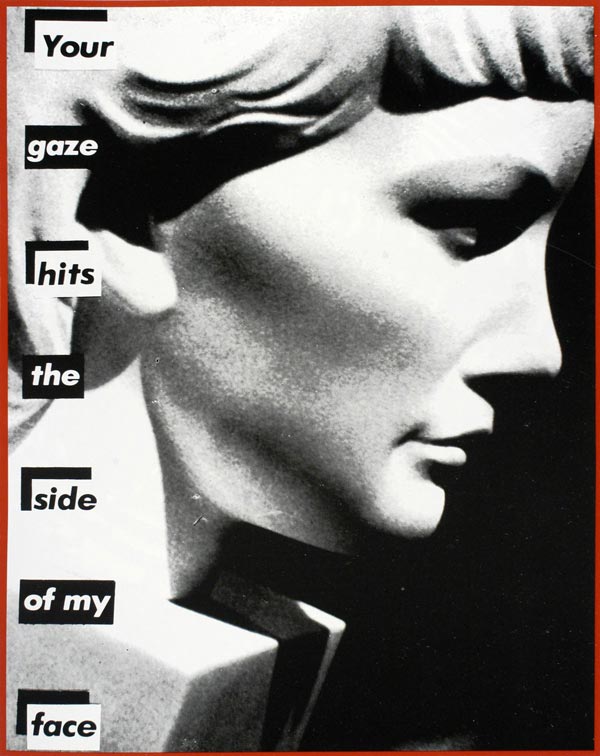

“The first massive influence on me was definitely the work of Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer. They were talking from a feminist perspective. In Kruger’s case, she did a piece called Untitled (Your Gaze Hits The Side Of My Face) [1981], which I found powerful and it really helped me think about the female gaze. And going on from there, the ablest gaze and the way people look at disabled people, or the way people were looking at me, which was obviously stigmatizing and difficult.

I loved Jenny Holzer’s text-based work. Her voice had power – a voice of authority. She made you think about signs, who writes them, and do you obey them? There was anarchy in her work too. That has definitely stayed with me, the whole of my career, both the atmosphere that Turner could bring and the perspective that Barbara Kruger offered. I often felt like I was in the minority, because I was a woman, and maybe dismissed because I was a disabled woman; assumed to be stupid, weak or feeble. Their influence helped. I had a guy assume that I couldn’t read because I was in a wheelchair. Anyway, those three artists have always been somewhere deep in my creative heart, influencing what I do.”

When was the first time this moved from being a hobby or educational pursuit, and into a profession?

“Instead of going to university, I worked in the civil service for a while. I needed a job but it was awful. At the time I didn’t really understand the extent of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome and the way it affected me. People could understand if I dislocated my knee, that I might not be able to come into work but the fatigue, the pain and other things that go with it meant that I was quite an unreliable civil servant at best. I hated it so much, that as soon as I became financially stable, I left. I thought they were going to sack me again. Having a job like that made me realise that actually being an artist was important to me. It was then, that I decided to go to university. I was like, right, I’ve got to get this right.

My university education was quite difficult, because I ended it being a full-time wheelchair user and I followed it with a really major surgery that restructured the bones in my leg. However, I did end up working voluntarily at a community arts organization on the back of university and they ended up giving me a job as a community arts worker.

Your work is informed by the individual and collective experiences of disabled communities around the country. When was the first time you realised that your art had the power to move or inspire others?

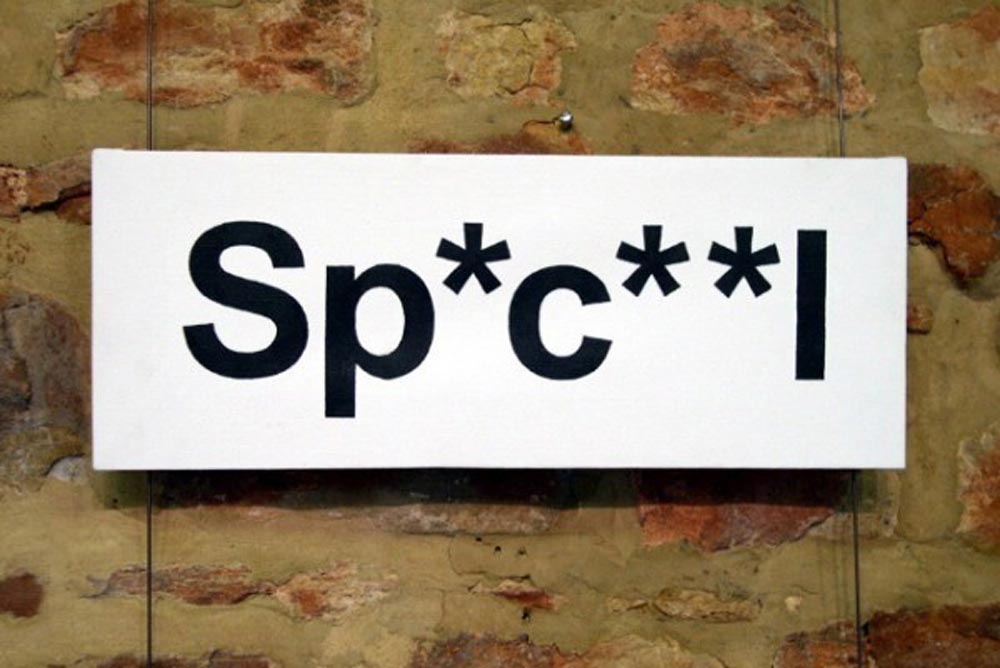

“Jo Verrant, Senior Producer and Director at Unlimited offered me my first artist residency. I was given time to work with a local arts organisation for a few months and make some new work in a studio space. During that time, I was online an awful lot. It was around 2001, so quite a few people were online then, mainly message boards. I was often on the BBC Ouch message board, which was the BBC’s disability forum. I was talking about terminology with other politicised disabled people. We’d talk about what we considered offensive language – special, challenged, spastic, mental.

Out of that I created the work Dirty Words For Disabled People, which was a collection of large stencilled canvases, on which some of these works had asterisks over the vowels. They were very big and basic but when it came to exhibiting these at the end of the residency, people in the disability arts community were telling me that they liked them. I knew I was on to something. I suppose that was my first disability conscious piece of work.”

What is the first thing you plan on doing once Covid vaccinations have been had, restrictions are lifted and shielding is a thing of the past?

“It’s going to be one of two things depending on what happens sooner. If it is possible, then in the summer I’ll go to Norfolk to see my mum and my family. They moved there a few years ago and we’ve not seen them since Christmas 2019. It will be nice to stay in their spare room, go to the beach, because if you’re in Norfolk, you’re never far away from a beach. The second would be to come to Barnsley and see The Way Ahead installed; to meet some of the people that contributed. It will be a good end to an unusual year.”

The original The Way Ahead collection was exhibited at The Civic from Sat 26 Jun to Sat 7 Aug 2021; the new public artwork called The Barnsley 15 was launched in July 2021 and is installed in Mandela Gardens for all to see.

To find out more about Caroline Cardus’ work, visit www.carolinecardusartist.com

Visit her on twitter @carolinecardus or Instagram @caroline_cardus